Use of alcohol hand rub (AHR) at ward entrances and use of soap and AHR by patients and visitors: a study in 27 wards in nine acute NHS trusts

Use of alcohol hand rub (AHR) at ward entrances and use of soap and AHR by patients and visitors: a study in 27 wards in nine acute NHS trusts

Joanne Savage , Christopher Fuller* , Sarah Besser , Sheldon Stone

Royal Free Hospital, London NW3 2PF, UK. Email: [email protected]

*Corresponding author

Accepted for publication: 13 July 2010

Key words: Hand hygiene , point of care , alcohol hand rub , visitors , ward entrance , campaign , measurement

Abstract

Ward procurement of hand hygiene consumables is a proxy measure of hand hygiene compliance. The proportion of this due to use of alcohol hand rub (AHR) at ward entrances, and bedside use of consumables by patients and visitors, is unknown. Thirty-six hours of direct observation of bedside hand hygiene behaviours by healthcare workers (HCWs), patients and visitors on 27 wards in nine hospitals was undertaken. AHR containers from ten ward entrances were collected for four days. Mean daily volume used was compared with mean daily volume procured. Only 4 % of bedside soap and AHR use was by visitors. Patients used neither. An average 21 % (range 7–38 % ) of all AHR procured by wards was used at ward entrances. Non-HCW use of soap or AHR at the bedside is low. Ward entrance use of AHR is modest but varies. Hand hygiene intervention studies using consumables as an outcome should assess and adjust for such usage.

Introduction

Although direct observation is considered the gold standard for assessing hand hygiene compliance, many studies of hand hygiene interventions use data on procurement or use of alcohol hand rub (AHR) and soap as proxy markers of compliance, or as an additional outcome measure ( Pittet et al, 2000 ; McGuckin et al, 2004 ; Eckmanns et al, 2006 ; Van de Mortel and Murgo, 2006 ; Boyce, 2008 ; Scheithauer et al, 2009 ). This is because direct observation is labour intensive, may be subject to the Hawthorne effect, may not be representative of overall performance for a ward or hospital, unless very frequently repeated, and may be subject to bias unless the observer is blinded to the intervention ( Van de Mortel and Murgo, 2006 ; Haas and Larson, 2007 ; Boyce, 2008 ; Torres-Viera et al, 2008 ; Joint Commission, 2009 ; Fuller et al, 2010 ). Procurement data is likely to be a more objective measure and refl ect long term trends in use of AHR and soap for hand hygiene, but it has its own diffi culties in interpretation. It may, forinstance, be affected by procurement patterns, which require data to be smoothed or averaged out. More importantly it is not possible to identify who used it and at what point, and may therefore, include use unrelated to hand hygiene moments ( Van de Mortel and Murgo, 2006 ; Joint Commission, 2009 ). Direct observation and consumables usage do not always correlate ( Van de Mortel and Murgo, 2006; Haas and Larson, 2007 ; Scheithauer et al, 2009 ), possibly refl ecting the above limitations.

In England and Wales, the cleanyourhands campaign ( www.npsa.nhs.uk/cleanyourhands ), which was rolled out to all acute NHS trusts in 2005, promoted the placement and usage of AHR at the bedside (point of care), ( National Patient Safety Agency, 2004 , 2006 ). An independent evaluation of the campaign, the NOSEC study (National Observational Study to Evaluate the cleanyourhands Campaign), used procurement data as a surrogate marker of hand

hygiene compliance in 185 acute trusts ( Stone et al, 2007 ). A threefold increase in the combined procurement of AHR and soap over the four years of the campaign was reported ( Slade et al, 2006 ; Stone et al, 2009 ). An unintended consequence of the campaign has been that many trusts now have AHR at the entrances to wards along with instructions on their websites and at ward entrances, directed toward staff, patients and visitors, to decontaminate hands upon entering and exiting wards ( Guys and St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust, 2009 ; Hampshire Community Healthcare NHS Trust, 2009 ; Scarborough and North East Yorkshire Healthcare NHS Trust, 2009 ). There is, therefore, concern that the rise in AHR orders reported by the NOSEC evaluation is greatly exaggerated by use of AHR at ward entrances by

healthcare workers (HCWs), visitors and patients, and by use of soap and AHR at the bedside by visitors and patients.

There is only one study we are aware of in the literature which examined the use of AHR at ward entrances but, despite reporting increased use during visiting hours, it gave no information on volumes or proportions used ( Kinsella et al, 2007 ). There are no studies we are aware of that examined patient or visitor use of soap or AHR. We therefore carried out a study with two aims: a) to determine what proportion of AHR use occurs at the ward entrance, instead of at the bedside, and b) to estimate what proportion of bedside use of soap and AHR is by visitors and patients.

Methods

To study the proportion of soap and AHR used at the bedside by visitors and patients we carried out 36 hours of direct observation on 27 wards in nine acute NHS trusts spread throughout south east and south west England, during peak weekday visiting hours of 13.00–20.00, in January and February 2009. There were no new changes in product procurement during this period that would be likely to change behaviour. A convenience sample was selected from the 60 wards and 16 hospitals participating in the Feedback Intervention Trial ( McAteer et al, 2006 ) – a national randomised controlled trial of a feedback intervention to improve hand hygiene compliance in HCWs on intensive therapy units (ITU) and acute care of the elderly (ACE) wards. Observations are performed on each trial ward for one hour every six weeks, using a standardised, reliable and sensitive tool, consistent with the World Health Organization’s fi ve moments for hand hygiene ( WHO, 2009b ) the Hand Hygiene Observational Tool (HHOT; available at: www.idrn.org/nosec.php ), ( McAteer et al, 2008 ). For the purposes of this study a tally of all instances of soap and AHR use by HCWs, patients and their visitors was recorded over the one hour period.

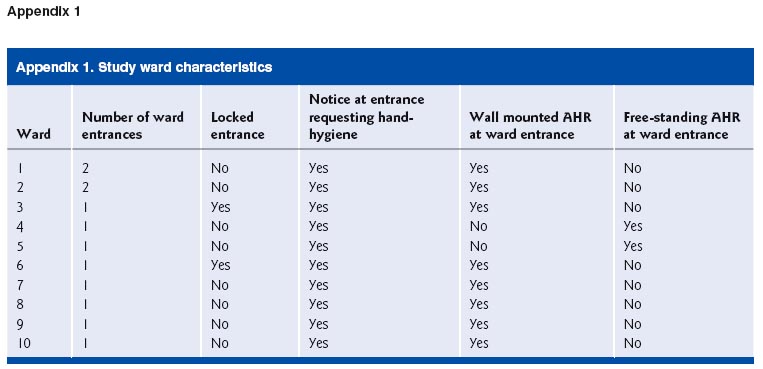

In order to quantify the proportion of AHR used at ward entrances, volumes used at entrances were measured on ten wards in four acute hospitals across England and Wales (see Appendix 1 for description of ward characteristics). Infection control nurses monitored AHR dispensers at the ward entrances for four consecutive 24-hour periods, following a detailed written protocol (Appendix 2) that had been fully discussed with the research team to ensure full comprehension. On the fi rst morning of the study, all bottles (or bags) of AHR at the ward entrance were replaced with a labelled full bottle. These bottles were checked each morning and replaced, when required, with a full, labelled and consecutively numbered bottle. All bottles were stored by the infection control team until collected by the study team for measurement. The average daily volume used at the entrance to each ward was expressed as a percentage of the average daily volume procured by the ward over the previous 12 months.

Ethical considerations

Observations were carried out covertly to prevent a Hawthorne effect. Ethical approval was received from the Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (Scotland B) and ward managers had given written consent.

Results

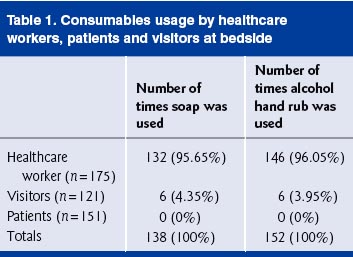

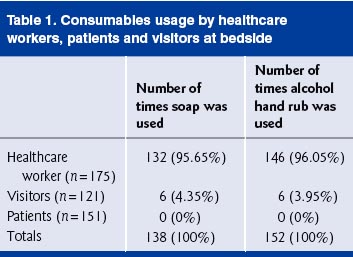

Proportion of AHR used by visitors/patients at the bedside (Table 1)

A total of 175 HCWs, 121 visitors and 151 patients were observed.No patient used soap or AHR during the observation sessions and96 % of all AHR and soap use was by HCWs.

Proportion of AHR used at ward entrances (Table 2)

Table 2 shows that, on average, for the ten wards sampled, the overallproportion of AHR procurement used at the ward entrance was21.4% . The proportion of AHR used at each ward entrance variedfrom 7.8 % to 32.8% of the ward’s daily AHR procurement.

To our knowledge this is the fi rst study to observe visitor and patient hand hygiene behaviour at the bedside and the fi rst to quantify the proportion of AHR used at ward entrances. We found that 21% of all AHR procured by the study wards was used at ward entrances and that 96% of soap and AHR use at the bedside was by HCWs. As the direct observations of consumable usage were carried out during peak visiting hours, it is likely that the proportion of AHR and soap used by visitors over a 24 hour period, at the bedside, may be even lower than the 4 % reported here. It was not feasible, within the resources of the study, to include direct observation of AHR use at ward entrances and therefore it is not possible to identify how much of that use was by HCWs and how much by patients. It is likely that more than half of this was by HCWs, given that visiting hours are limited for most patients. This study therefore suggests that nearly all soap usage (96% ) and probably more than 85 % of AHR procured by wards is used by HCWs, with 75% of procurement representing use at the point of care or bedside.

The strength of this study is that it has measured bedside use in a large number of wards in nine trusts in seven different regions, and had access to monthly ward procurement data for AHR and soap. We believe that the results are likely to be representative of wards in acute NHS trusts but their generalisability might have been limited by the fact that this was a convenience sample of wards involved in a trial of a hand hygiene intervention ( McAteer et al, 2008 ) targeting HCWs. Hand hygiene might therefore be better in these wards either because of the intervention or because the wards and/or their trusts were suffi ciently interested in hand hygiene to volunteer for the trial. Patients in the wards were either highly dependent acute elderly medical or ITU patients, requiring a lot of patient–HCW contact. Such wards may therefore have higher proportions of AHR used at ward entrances and of consumables used at the bedside by non-HCWs. The study was carried out during the week, when there may be fewer visitors than at the weekend, which may theoretically mean that the study underestimated ward entrance and non-HCW use of consumables. Finally, although we were able to measure use of AHR at ward entrances for ten wards, this was only in four trusts, which may also limit the representativeness of our fi ndings for this part of the study.

We did not examine use of AHR in hospital foyers or entrances. It is likely that a further proportion of AHR and soap ordered at the hospital level is due to usage here by a mixture of HCWs and visitors. However, recent studies in three hospitals in the UK ( Grice et al, 2008 ), and one hospital in New Zealand ( Murray et al, 2009 ) found that only 16% and 18% , respectively, of people passing through hospital foyers used AHR. An American survey of 71 hospitals reported that only 1 % of visitors disinfected their hands on entering the hospital

( Pittz, 2009 ). These studies suggest that use of AHR in hospital entrances is low, although no study measured volumes used as a percentage of total hospital procurement.

This study has implications for understanding the NOSEC study and for the design and interpretation of hand hygiene intervention studies using consumables data as a proxy marker of compliance. For the NOSEC study ( Slade et al, 2006 ; Stone et al, 2009 ) it provides reassurance that the reported changes in trust-level procurement of soap and to a very large extent AHR, refl ect increased use by HCWs as opposed to patients and visitors. The fact that patients were not seen to use soap or alcohol hand gel during the observations sessions is striking. This may refl ect their relatively high dependency, or the possibility that they only cleaned their hands in the toilets or behind curtains, areas where observations could not be carried out for ethical reasons of privacy and dignity. However, we think it unlikely that such use by patients would have changed substantially during the NOSEC study, and affect our conclusions that the increase in procurement was due to change in HCW behaviour. Although use of AHR at the entrance to a ward is not included in the WHO 5 moments for hand hygiene or in the standard operating procedures of the HHOT, it can be argued that such use by HCWs is appropriate in that it not only reduces transient carriage of pathogens on their hands before entering a clinical area, but inculcates a culture of hand hygiene by ‘ritualising’ their entrance to the ward.

For future studies of hand hygiene interventions using ward procurement data as an additional outcome measure or surrogate marker of compliance, this study makes it clear that some assessment of visitor and patient use at the bedside and ward entrances should be carried

out, with overall procurement data adjusted; especially as ward entrance use can vary widely between wards. For studies using total hospital procurement data as an outcome measure, use of AHR at hospital entrances should also be measured and adjusted for.

The UK has sought, through the National Patient Safety Agency ( National Patient Safety Agency, 2008 ) to ensure that trusts concentrate on encouraging HCWs, rather than visitors or patients, to clean their hands, but left it to their discretion as to whether trusts place AHR dispensers at hospital and ward entrances. However, with the emergence of the swine fl u pandemic, since the end of the NOSEC study, and WHO advice with its subsequent high profi le focus on hand hygiene ( DH HPIH and SD and HPA, 2007 ; World Health Organization, 2009a ), it is unlikely that hospitals will remove AHR from entrances to their wards. Hand hygiene intervention studies that use consumables as an outcome measure, therefore, need to assess and adjust for use of soap and AHR by non-HCWs at the bedside, and for use of AHR at ward entrances.

Funding

Patient Safety Research Programme.

Confl ict of interests

None declared.

References

Boyce JM . ( 2008 ) Hand hygiene compliance monitoring: current perspectives from the USA . Journal of Hospital Infection 70(Suppl 1 ): 2 – 7 .

DH HPIH and SD and HPA ( 2007 ) Pandemic infl uenza guidance for infection control in hospitals and primary care settings . DH HPIH and SD and HPA : London .

Eckmanns T , Schwab F , Bessert J , Wettstein R , Behnke M , Grundmann H , Ru¨den H , Gastmeier P . ( 2006 ) Hand rub consumption and hand hygiene compliance are not indicators of pathogen transmission in intensive care units . Journal of Hospital Infection 63 : 406 – 11 .

Fuller C, Besser S, Cookson BD, Fragaszy E, Gardiner J, McAteer J, Michie S, Savage J, Stone SP. (2010) Technical note: assessment of blinding of hand hygiene observers in randomised controlled trials of hand hygiene interventions . American Journal of Infection Control

38 : 332 – 4 .

Grice JE , Roushdi I , Ricketts DM . ( 2008 ) The effect of posters and displays on the use of alcohol gel . British Journal of Infection Control

9(5): 24 – 7 .

Guys and St Thomas NHS Foundation Trust (2009) Help us to protect you - promoting hand hygiene [Online] Available at: http://www.guysandstthomas. nhs.uk/pandv/infection_control/handhygiene.aspx (accessed 21 December 2009).

Haas JP , Larson EL . ( 2007 ) Measurement of compliance with hand hygiene . J ournal of Hospital Infection 66: 6 – 14 .

during an infl uenza pandemic, New Zealand, August 2009 .

Eurosurveillance 14( 37 ): 19331 .

National Patient Safety Agency ( 2004 ) Ready, steady, go! The full guide to implementing the cleanyourhands campaign in your trust. London : National Patient Safety Agency .

National Patient Safety Agency ( 2006 ) Flowing with the go: the complete year two campaign maintenance handbook for cleanyourhands partner trusts: the sequel to Ready, steady, go. London : National Patient Safety Agency .

National Patient Safety Agency . ( 2008 ) Patient safety alert . 2nd edn . London : National Patient Safety Agency . Pittet D , Hugonnet S , Harbarth S , Mourouga P , Sauvan V , Touveneau S . ( 2000 ) Effectiveness of a hospital-wide programme to improve compliance with hand hygiene . Lancet 356 : 1307 – 312 .

Pittz EP. (2009) Availability and use of hand hygiene products, by visitors, at the entry points of hospitals. In: AJIC (A merican Journal of Infection Control), 36th Annual Educational Conference and International Meeting, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. 7–11 June 2009, Presentation Number 8-79 vol. 37. Scarborough and North East Yorkshire Healthcare NHS Trust. (2009) About Ash Ward: infection control (including fl owers). [Online] Available at: http://www.scarborough.nhs.uk/wards_ash.php (accessed 21 December 2009).

Scheithauer S , Haefner H , Schwanz T , Schulze-Steinen H , Schiefer J . ( 2009 ) Compliance with hand hygiene on surgical, medical, and neurologic intensive care units: direct observation versus calculated disinfectant usage . American Journal of Infection Control 37 (10 ):

835 – 41 .

Slade R , Fuller C , Charlett A , Cookson B , Cooper B , Duckworth G , Hayward A , Jeanes A , Michie S , Roberts J , Stone SP . ( 2006 ) National Observational Study of the Effectiveness of the Cleanyourhands Hampshire Community Healthcare NHS Trust (2009) What is Hampshire Community Health Care doing to prevent infections?

[Online] Available at: http://www.hchc.nhs.uk/our-services/infectioncontrol (accessed 21 December 2009).

Joint Commission ( 2009 ) Measuring hand hygiene adherence: overcoming the challenges. The Joint Commission : USA .

Kinsella G , Thomas AN , Taylor RJ . ( 2007 ) Electronic surveillance of wall-mounted soap and alcohol gel dispensers in an intensive care unit . J ournal of Hospital Infection 66: 34 – 9 .

McAteer J , Stone SP , Fuller C , Slade R , Michie S . ( 2006 ) Development of an intervention to increase UK NHS healthcare worker handhygiene behaviour using psychological theory . Journal of Hospital Infection 64 : S53 .

McAteer J , Stone S , Fuller C , Charlett A , Cookson B , Slade R , Michie S . ( 2008 ) Development of an observational measure of healthcare worker hand-hygiene behaviour: the hand-hygiene observation tool HHOT) . Journal of Hospital Infection 68 ( 3 ): 222 – 9 .

McGuckin M , Taylor A , Martin V , Porten L , Salcido R . ( 2004 ) Evaluation of a patient education model for increasing hand hygiene compliance in an inpatient rehabilitation unit . A merican Journal of Infection Control 32( 4): 235 – 8 .

Murray R , Chandler C , Clarkson Y , Wilson N , Baker M , Cunningham R , on behalf of the Wellington Respiratory and Hand Hygiene Study Group ( 2009 ) Sub-optimal hand sanitiser usage in a hospital entrance Campaign (NOSEC): results of the fi rst questionnaire. A bstract. Journal of Hospital Infection 64( Suppl. 1): S51 – S52 .

Stone SP , Slade R , Fuller C , Charlett A , Cookson BD , Teare L , Jeanes A , Cooper B , Roberts J , Duckworth G , Hayward A , McAteer J , Michie S . ( 2007 ) Early communication: does a national campaign to improve hand hygiene in the NHS work? Initial English and Welsh experience from the NOSEC study (National Observational Study to Evaluate the CleanY ourHands Campaign) . J ournal of Hospital Infection 66(3): 293 – 6 .

Stone SP, Fuller C, Savage J, Slade R, Charlett A, Cookson BD, Cooper B, Duckworth G, Murray M, Hayward A, Jeanes A, Roberts J, Teare L, McAteer J, Michie S. (2009) The success and effectiveness of the world's fi rst national cleanyourhands campaign in England and Wales 2004–2008: FINAL RESULTS. In: SHEA (The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America), Annual Meeting, San Diego, California. 19–22 March 2009 abstract.

Torres-Viera CG, Dolan M, Dembry L. (2008) Correlation between direct observation of hand hygiene compliance and electronically monitored use of hand sanitizer, 2008. In: SHEA (The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America), A nnual Meeting , San Diego, California. April 2008 abstract.

Van de Mortel T , Murgo M . ( 2006 ) An examination of covert observation and solution audit as tools to measure the success of hand hygiene interventions . American Journal of Infection Control 34 : 95 – 9 .

World Health Organization (2009a) Pandemic infl uenza preparedness and response: a WHO guidance document. WHO Press: Geneva.

World Health Organization (2009b) Clean care is safer care. [Online] Available at: http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/background/5moments/ en/index.html (accessed 21 December 2009).